Without This, I Wouldn’t Exist 1: Karl Marx, Capital

In an interview with Sadiq Khan, mayor of London, the model and editor, Naomi Campbell, said “I wouldn’t be a model if it wasn’t for gay men. I wouldn’t even exist.” What did she mean? (1)

Without imputing too much to Campbell, her statement indicates an awareness that we, as individuals and personalities, are made things. Philosophically speaking this is not an original position, it being expressed by Karl Marx, Fredreich Neitzsche, and Sigmund Freud in the nineteenth century, perhaps most succinctly, by Simone de Beauvoir — “One is not born, but rather becomes a woman” — as well as Frantz Fanon in the twentieth century. (2) This list of luminaries is hardly exhaustive and earlier versions may be found — Caliban’s profit comes to mind — but the thought that our personalities and our identities, our very selves, are made, is resisted because it represents a challenge to that which many hold dear and without which (they think) society could not function: their freedom, autonomy, and control and responsibility. Some reject the notion outright believing that they are “self-made” while others curse the forces that made them because they deprive them of their own self-creation, as if without Campbell’s gay men, no other force would prevail and they could gain a freedom that is not obviously implied by her statement.

The advantage Campbell has over those who suppose freedom exists is that she is aware of what or who made her. While this may appear a slight advantage, it is no small thing; after all, the command of the Delphic oracle was “Know thyself”. There is much to be said for knowing on what on stands, no least being able to look at oneself honestly, negotiate with that self and the world that made it. There is, therefore, a great deal to be gained by asking “On what do I depend for my existence?”

But knowing comes at a price: one could always have been otherwise, and so the truth of selfhood is always contingent and doubtful. Campbell says that she “wouldn’t even exist” but for gay men but it is unlikely that one thingmade her or makes us. In the video version of the interview she also points to her upbringing in South London, her particular experience of racial abuse as well as a collective experience of terrorism. (3) Perhaps what she means is that without gay men the public persona that is “Naomi Campbell” would not exist, with the implication that one is not born Naomi Campbell but rather one becomes “Naomi Campbell”. She is other than herself. But I do not think this is a condition unique to celebrity, and faced with the knowledge that we could be otherwise, sincerity and authenticity might seem to wither, while the expression of any individual self or collective identity becomes, of necessity, uncomfortable and ironic.(4)

To pursue the exercise though, if there is one thing that made me it is books, first the books that were available to me at home, then the books at primary school, notably Iain Crichton Smith’s Consider the Lilies, and only then the books I sought out myself. That availability and my ability to seek books depended on parents, schools, and free university education, of which I was among the last recipients in the UK. Some of these books relate to a specific time and place. Others are important only in terms of how I think. Karl Marx’s account of the Highland Clearances is both, being a foundation of post-Enlightenment thought as well as describing the land I grew up in, learning Gaelic after that language’s suppression in a landscape overlooked by the Duke of Sutherland and where the name of the family factor, Patrick Sellar, was (and still is) one to be spat upon. (5)

Here, at last, then is Karl Marx describing the so-called primitive accumulation of capital. (6)

The last process of wholesale expropriation of the agricultural population from the soil is, finally, the so-called clearing of estates, i.e., the sweeping men off them. All the English methods hitherto considered culminated in “clearing.” As we saw in the picture of modern conditions given in a former chapter, where there are no more independent peasants to get rid of, the “clearing” of cottages begins; so that the agricultural labourers do not find on the soil cultivated by them even the spot necessary for their own housing. But what “clearing of estates” really and properly signifies, we learn only in the promised land of modern romance, the Highlands of Scotland. There the process is distinguished by its systematic character, by the magnitude of the scale on which it is carried out at one blow (in Ireland landlords have gone to the length of sweeping away several villages at once; in Scotland areas as large as German principalities are dealt with), finally by the peculiar form of property, under which the embezzled lands were held.

The Highland Celts were organised in clans, each of which was the owner of the land on which it was settled. The representative of the clan, its chief or “great man,” was only the titular owner of this property, just as the Queen of England is the titular owner of all the national soil. When the English government succeeded in suppressing the intestine wars of these “great men,” and their constant incursions into the Lowland plains, the chiefs of the clans by no means gave up their time-honored trade as robbers; they only changed its form. On their own authority they transformed their nominal right into a right of private property, and as this brought them into collision with their clansmen, resolved to drive them out by open force. “A king of England might as well claim to drive his subjects into the sea,” says Professor Newman. This revolution, which began in Scotland after the last rising of the followers of the Pretender, can be followed through its first phases in the writings of Sir James Steuart and James Anderson. In the 18th century the hunted-out Gaels were forbidden to emigrate from the country, with a view to driving them by force to Glasgow and other manufacturing towns. As an example of the method obtaining in the 19th century, the “clearing” made by the Duchess of Sutherland will suffice here. This person, well instructed in economy, resolved, on entering upon her government, to effect a radical cure, and to turn the whole country, whose population had already been, by earlier processes of the like kind, reduced to 15,000,into a sheep-walk. From 1814 to 1820 these 15,000 inhabitants, about 3,000 families, were systematically hunted and rooted out. All their villages were destroyed and burnt, all their fields turned into pasturage. British soldiers enforced this eviction, and came to blows with the inhabitants. One old woman was burnt to death in the flames of the hut, which she refused to leave. Thus this fine lady appropriated 794,000 acres of land that had from time immemorial belonged to the clan. She assigned to the expelled inhabitants about 6,000 acres on the sea-shore — 2 acres per family. The 6,000 acres had until this time lain waste, and brought in no income to their owners. The Duchess, in the nobility of her heart, actually went so far as to let these at an average rent of 2s. 6d. per acre to the clansmen, who for centuries had shed their blood for her family. The whole of the stolen clanland she divided into 29 great sheep farms, each inhabited by a single family, for the most part imported English farm-servants. In the year 1835 the 15,000 Gaels were already replaced by 131,000 sheep. The remnant of the aborigines flung on the sea-shore tried to live by catching fish. They became amphibious and lived, as an English author says, half on land and half on water, and withal only half on both.

But the brave Gaels must expiate yet more bitterly their idolatry, romantic and of the mountains, for the “great men” of the clan. The smell of their fish rose to the noses of the great men. They scented some profit in it, and let the sea-shore to the great fishmongers of London. For the second time the Gaels were hunted out.

But, finally, part of the sheep-walks are turned into deer preserves. Every one knows that there are no real forests in England. The deer in the parks of the great are demurely domestic cattle, fat as London aldermen. Scotland is therefore the last refuge of the “noble passion.” “In the Highlands,” says Somers in 1848, “new forests are springing up like mushrooms. Here, on one side of Gaick, you have the new forest of Glenfeshie; and there on the other you have the new forest of Ardverikie. In the same line you have the Black Mount, an immense waste also recently erected. From east to west — from the neighbourhood of Aberdeen to the crags of Oban — you have now a continuous line of forests; while in other parts of the Highlands there are the new forests of Loch Archaig, Glengarry, Glenmoriston, &c. Sheep were introduced into glens which had been the seats of communities of small farmers; and the latter were driven to seek subsistence on coarser and more sterile tracks of soil. Now deer are supplanting sheep; and these are once more dispossessing the small tenants, who will necessarily be driven down upon still coarser land and to more grinding penury. Deer-forests and the people cannot co-exist. One or other of the two must yield. Let the forests be increased in number and extent during the next quarter of a century, as they have been in the last, and the Gaels will perish from their native soil… This movement among the Highland proprietors is with some a matter of ambition… with some love of sport… while others, of a more practical cast, follow the trade in deer with an eye solely to profit. For it is a fact, that a mountain range laid out in forest is, in many cases, more profitable to the proprietor than when let as a sheep-walk. … The huntsman who wants a deer-forest limits his offers by no other calculation than the extent of his purse…. Sufferings have been inflicted in the Highlands scarcely less severe than those occasioned by the policy of the Norman kings. Deer have received extended ranges, while men have been hunted within a narrower and still narrower circle…. One after one the liberties of the people have been cloven down…. And the oppressions are daily on the increase…. The clearance and dispersion of the people is pursued by the proprietors as a settled principle, as an agricultural necessity, just as trees and brushwood are cleared from the wastes of America or Australia; and the operation goes on in a quiet, business-like way, &c.”

The spoliation of the church’s property, the fraudulent alienation of the State domains, the robbery of the common lands, the usurpation of feudal and clan property, and its transformation into modern private property under circumstances of reckless terrorism, were just so many idyllic methods of primitive accumulation. They conquered the field for capitalistic agriculture, made the soil part and parcel of capital, and created for the town industries the necessary supply of a “free” and outlawed proletariat.

Notes

- “What’s the Secret of Every Great City? Talent”, British Vogue (December 2017): 185–89 [accessed via RB Digital www.rbdigital.com/reader.php#/reader/readhtml/392997/22231 ]

- For many, de Beauvoir’s observation is proverbial, but quite what she meant by it is much debated. “Becomes” is not the same as “made” and, as one expects from an existentialist, allows for the possibility of agency and so responsibility. Equally, if “woman” is a social position, it is also a relationship to a particular type of body so while the type of body might remain the same, the social position and relationship to that body might very well change. Other debates are available. With respect to Fanon, I am thinking of the locus classicus, Black Skin, White Masks, which I have only read in extract, but is published by Pluto Press in the UK and Grove in the US.

- “Naomi Campbell Meets …Sadiq Khan”, British Vogue, YouTube

- The not very well concealed title here is Richard Rorty’s Contingency, Irony, Solidarity (Cambridge: CUP, 1989)

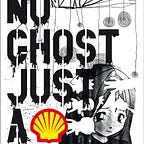

- It is impossible to dismiss the importance of the Highland Clearances. Their place in intellectual history is assured. Politically, socially, and militarily, the processes undertaken to repress the local population and their culture were replicated across the British Empire, not least with respect to the indigenous people of Canada. Locally, and to reproduce an old saw, no true Scotsman does not piss on the statue of the Duke of Sutherland. For her interview with Khan, Campbell wore Alexander McQueen, who famously caused scandal with his Highland Rape collection of Fall 1995.

- Karl Marx, Capital: an abridged edition (Oxford: OUP, 1995), pp. 369–71.